Never Look at Valuation in Isolation (Part II of II)

Investors can become overly reliant on valuation metrics, which can silently kill portfolio returns if analyzed in isolation

Note: this is a two parts series. If you missed Never Look at Valuation in Isolation Part I, click the button below.

Too Long, Didn’t Read? Quick Highlights:

Transformative high growth markets typically become much larger than originally forecasted. In 2009, Uber’s management team forecasted their total addressable market as ~$4bn, whereas today, management forecasts TAM as ~$12T. Market size forecasting is especially difficult in high growth technology markets (SaaS, gaming, processing, AI/ML, etc.) since they generally become orders of magnitude larger than the consensus usually predicts. As such, evaluating the NTM (Next-Twelve Months) multiple in isolation doesn’t capture much qualitative insight about a business and surely does not capture market potential

Since forecasting future market size and penetration rates can be a fruitless exercise, we assume that transformative and well managed companies have a high probability of continually moving fast and disrupting. Investors can make better decisions by focusing on understanding the present by forming perspective around two key elements: 1) what has a high probability of remaining the same in the long run and 2) can this company benefit from increasing returns

Do not sacrifice valuation completely for growth. Disregarding valuation completely will hurt returns in the long run. Investors must be prudent when paying up for companies that are “richly” valued and understand expectations for those companies going forward. Too many investors are overpaying for software companies that are average at best and lack sustainable competitive advantages. These companies will assuredly disappoint investors in the future if they disregard valuation completely

Twilio’s case study suggests that finding assets with leaders who 1) reduce friction in core markets, 2) use their core market dominance to expand into adjacent markets, and 3) have leadership who continues to focus on seeing the present clearly will outperform in the long term. However, despite long term outperformance, short term underperformance can occur by paying a high price and investors must be willing to allocate additional capital to quality assets if the investment thesis remains intact

Disruptive Markets Can Transform Into Far Larger Opportunities Than Originally Forecasted

Imagine traveling back to 2010 for the sole purpose of being the honored guest of a game show we will call “LET’S PROJECT THIS MARKET SIZE”. In this fictitious novelty show, you would be responsible for forecasting the 2020 total addressable market (TAM) figures for each of the following companies: Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google.

Chances are your projections would have been wildly off and most likely well below current TAM estimates. You would have had to possess superhuman insight (or a time machine) to properly forecast mobile device acceptance and development, the hyper-surge of cloud computing, and how acquisitions and platform expansion have all surpassed previously forecasted TAM estimates for these businesses.

This is a double click on what Brad Gerstner conveyed in his CNBC interview. Evaluating the current multiple, or in some cases even the NTM (Next-Twelve Months) multiple, in isolation doesn’t capture much qualitative insight about a business and surely doesn’t capture market potential. This is especially true for the high growth technology markets (SaaS, gaming, processing, AI/ML, etc.) since they become magnitudes of order larger than the consensus generally predicts.

Chetan Puttagunta at Benchmark made the following observation on TAM:

“It’s really funny to read the initiating coverage of Salesforce when it went public in the early 2000’s and to see what the estimates of Salesforce’s potential addressable market are. And then today Salesforce itself has $13 billion of revenue and Salesforce would argue that they are less than 20% penetrated into their core markets. So these software markets actually ended up being orders of magnitude larger than what people thought they were, and I think people dreamed very aggressively about what software could do back then and how pervasive software would be used, but that dream was actually still not big enough.”

Salesforce’s multiple at its time of going public, and many years thereafter, didn’t come close to properly capturing the potential that lay ahead. Instead of attempting to predict market sizes 10 years out, we feel it is imperative to see the present clearly by identifying disruptive companies that are focusing on high growth markets and who are building accumulating advantages. Once these opportunities have been identified, it is helpful to remember that there is a strong possibility the market size will become much larger than the original consensus forecast.

Uber case study on how disruptive markets transform beyond initial use case

In 2009, a small company called UberCab was pitching a new idea of how they could be the “next generation black cab service.” They were only operating in San Francisco and New York at the time, but they foresaw themselves as the black car leader for professionals in American cities. They estimated that their total addressable market was ~$4bn.

Fast forward to 2020, Uber is a publicly traded company (Market cap of ~$96bn) that is still in the early stages of capturing what it estimates to be a $12 trillion (yes, that’s trillion with a “T”) total addressable market that includes personal mobility, food delivery, and freight shipping.

The important point to understand here is that the original market size was estimated to be 3,000x smaller than it is today. The founders made an implicit assumption that the future would look very similar to the past and that the arrival of their product (Uber) wouldn’t change the overall market size of the car-for-hire transportation market.

Famous venture investor Bill Gurley said the following in regards to Uber’s market expansion, “When you materially improve an offering, and create new features, functions, experiences, price points, and even enable new use cases, you can materially expand the market in the process.”

The main point to understand is that the historical market is radically different than today’s market. Uber has a different experience and additional use cases vs. the traditional black car service. These differences ultimately help explain the TAM growth.

Gurley’s main takeaways:

Different Experience:

Pick-up times. In cities where Uber has high liquidity, you have average pick-up times of less than five minutes. For most of America, prior to Uber it was impossible to predict how long it would take for a taxi to show up. You also didn’t have visibility into its current location; so having confidence about the taxi’s arrival time was nearly impossible. As Uber becomes more established in a market, pick-up times continue to fall, and the product continues to improve.

Coverage density. As Uber evolves in a city, the geographic area they serve grows and grows. Uber initially worked well primarily within the San Francisco city limits. It now has high liquidity from South San Jose to Napa. This enlarged coverage area not only increases the number of potential customers, but it also increases the potential use-cases. Uber is already achieving liquidity in geographic regions where consumers rarely order taxis, which is explicitly market expansion.

Payment. With Uber you never need cash to affect a transaction. The service relies solely on payment enabled through a smartphone application. This makes it much easier to use on the spur of the moment. It also removes a time consuming and unnecessary step from the previous process.

Civility. The dual-rating system in Uber (customers rate drivers and drivers rate customers) leads to a much more civil rider/driver experience. This is well documented and understood. With taxis, users worry about being taken advantage of, and many drivers spend all day with riders accusing them of such. This can make for an uncomfortable experience on both sides.

Trust and safety. Most Uber riders believe they are safer in an Uber than in a traditional taxi. This sentiment is easy to understand. Because there is a record of every ride, rider, and driver, you end up with a system that is much more accountable than the prior taxi market (it also makes it super easy to recover lost items). The rating system also ensures that poor drivers are removed from the system.

Expanding Use Cases:

Use in less urban areas. Because of the magical ordering system and the ability to efficiently organize a distributed set of drivers, Uber can operate effectively in markets where it simply didn’t make sense to have a dense supply of taxis. If you live in a suburban community, there is little chance you could walk out your door and hail a cab. And if you call on the phone, it is a very spotty proposition. Today, Uber already works dramatically well in many suburban areas outside of San Francisco with pick up times of less than 10 minutes. This creates new use cases versus a historical model.

Rental car alternative. When traveling on business, many people previously opted for renting a car; today that is replaced with Uber, which is materially better. You do not have to wait in lines, and are able to avoid the needless bus rides on each end of the trip. Users do not have to map routes or find parking or pay for parking.

A couple’s night out. The liquidity is so high in the San Jose Peninsula that a couple living in Menlo Park will Uber to a dinner in Palo Alto (perhaps 3 miles away) to avoid the risk of driving after having a glass of wine. This was not a use case that existed for taxis historically. It’s also great for getting from San Francisco back to the suburbs after a night on the town. This was a historic black car market, but the ease and convenience greatly increases the number of times it is now done.

Transporting kids. An article in the New York Times titled “Mom’s Van Is Called Uber” suggests that parents are using Uber to send their kids to different events. Many people wouldn’t put their young kids into taxis (due to trust), but they are quite comfortable doing this in an Uber. It is also common for parents with teenagers to encourage taking Uber when they go out, to reduce the risk that they end up in a car with someone who may have been drinking.

Transporting older parents. Many adults insist that their older parents put Uber on their phones to have an alternative to driving at night or in traffic. Convincing them to use Uber is a much easier a task than suggesting they call a taxi due to both convenience, ease of use, and social acceptance.

Supplement for mass transit. If someone primarily uses mass transit, they are likely to consider UberX (low price offering) for exceptions such as when they just miss a train, or when they might be late for a meeting. By having a lower price point and more reliability than a taxi, this becomes new market opportunity that was not previously utilized.

While it was impossible for investors to have known how this market would have expanded in 2009, the key takeaway is that disruptive markets can transform into far larger opportunities than originally forecasted and investors should be careful applying old stagnant market sizing numbers to growing and disruptive technology.

While We Can't Forecast the Future with 100% Accuracy, We Can Attempt to Properly Evaluate the Present

We have a high degree of confidence that fantastic companies in exceptional markets will perform quite well over the next decade. We allocate capital aggressively to these type of assets, but also understand that others may view them to be “valued richly”.

We have found that solely focusing on valuation metrics can lead investors to misdiagnose the current state of a business from both a quantitative and qualitative perspective.

As such, we attempt to clearly understand the present by forming perspective around two key elements: 1) what has a high probability of remaining the same in the long run and 2) can this company benefit from increasing returns?

1) What Has a High Probability of Remaining the Same? – We like to identify businesses that solve long-term problems, meaning the organizations core focus won’t fundamentally change in the foreseeable future. While we can’t predict what Facebook’s product portfolio will be in ten years, we are highly confident that people will desire hyper-connectivity via social mediums. Understanding that Facebook excels at human connection helps us gain confidence that their core value proposition has potential to fuel market expansion and growth over the long term.

Perhaps the best example of such thinking comes from Amazon and how Jeff Bezos understood the present well enough to have a high degree of confidence in the future. Eight years ago Bezos was confident that over time customers would not lose their desire for lower prices, fast delivery, and large product selection. In a 2012 interview he said the following:

“I frequently get the question, what is going to change in the next 10 years?…. I almost never get the question what is NOT going to change in the next 10 years? I submit to you that the second question is actually the more important of the two. Because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time…. In our retail business we know that customers want low prices, and I know that is going to be true 10 years from now.”

Bezos understands present trends that are unlikely to change, which in turn allows him to focus on creating business model leverage that pays increasingly valuable dividends over the long term. Such mental models typically can be applied to other business lines in the same organization. Bezos evidenced this by relaying his thoughts around Amazon’s AWS engine:

“On AWS, the big ideas are also pretty straightforward. It’s impossible for me to imagine that 10 years from now somebody is going to say ‘I love AWS, I just wish it was a little less reliable’ or ‘I love AWS, I just wish you would raise prices’. The big ideas in business are often very obvious, but it’s very hard to maintain a firm grasp of the obvious at all times.”

We agree that the big ideas of business are indeed fairly obvious and at times easy to spot. Too many investors waste time with crystal balls and fail to realize that the best predictor of the future is properly considering the present. Looking for obvious trends that have a low-likelihood of changing in a given time period is something we focus on as it increases our probability of success when allocating capital.

As we assess a company’s valuation, it is paramount to study the current business model to a degree that allows us to form a view around staying power.

2) Does the Business Create Leverage and Reduce Friction? – When we analyze potential investments, we begin by looking at the current state of the business and ask ourselves “Does this business help reduce end user friction?” In other words, we like to identify assets that make life dramatically easier for whomever is using the product or service. Developing a view of how a business reduces friction is powerful insight, and can be harvested by anyone willing to flex their intellectual curiosity.

We have observed over the years that when companies become adept at reducing customer friction, they cultivate business model leverage that has strong potential to manufacture into what Keith Rabois refers to as an “accumulating advantage”. In essence, an accumulating advantage means the business gets easier over time and generally corresponds to an array of competitive moats (economies of scale, network effects, high switching costs, etc.) The power of accumulating advantages serves as an “economical cheat code” of sorts, since it leads to decreased amounts of end user friction as a business grows.

Below we identify two examples of how assessing the present can lead investors to analyze business models that reduce user friction. It should be noted that this mental model can be applied to nearly any business across industry, but is particularly potent when evaluating software, internet, and marketplace businesses.

Netflix and Reduced Choice – Most investors are familiar with Netflix and the advantages their business model has developed. Ben Thompson and Hamilton Helmer have masterfully covered the company from a strategic standpoint, and we don’t feel the need to recapitulate such thoughts. Instead, we want to focus on a different point, and that is how Netflix has redefined user selection, which has effectively reduced friction.

Netflix delivers strong, fair, and poor content, but regardless of quality, it is extremely easy for users to consume. Humans are lazy and tend to process visual media with a “path of least resistance” mentality that somewhat resembles fast food consumption. Often times, viewers are so lazy that little to no thought goes into their program selection. They simply watch what is convenient, highly rated, or recommended. Better yet, they log on to watch what friends have suggested, making for a an increasingly frictionless experience. Consumers barely have to make a choice, and the consequences of minimal consideration are rather benign.

Content quality on Netflix is irrelevant to a degree, because consumption is so efficient.

Compare this with the Blockbuster era, where consumers would spend hours in video stores with their families searching for content that hopefully wouldn’t disappoint. Since there was an upfront, and often substantial time commitment to access such content, the consumer had additional pressure to pick the right title that would satisfy all viewers.

In fact, this movie selection process induced so much substantial pressure on the consumer, that many would leave Blockbuster in disappointment, yet still venture to Hollywood Video for redemption. The consumer had the power of choice, but this choice had consequences; choose the right content and perhaps a stimulating experience would follow, pick the wrong content and everyone would be disappointed.

Netflix is one of our original sins of omission. We briefly evaluated the business but didn’t invest since the valuation was “too much to stomach”. We missed out on 400%+ returns in a 4 year period as we refused to contextualize valuation. We missed obvious business leverage and failed to evaluate the present of what consumers wanted.

PayPal’s Convenience – PayPal was one of our first investments, and from a qualitative standpoint rested on a fairly straightforward thesis. Several years back we actively engaged in selling various items on marketplaces, such as Ebay. We quickly noticed one theme that extended across all these marketplaces: they used PayPal. This made it extremely easy to sell items, purchase items, and generate proper shipping documentation. We fell in love with PayPal’s product, since it seamlessly facilitated transactions and made life easier for both buyers and sellers.

This reduced friction spurred us to use PayPal for other reasons, such as sending money to family and friends, bill payment, and regular e-commerce purchasing. As we participated in these tangential transactions, we began to understand the power of the PayPal platform (PayPal owns the common consumer brand Venmo). This caused us to casually evangelize the product, especially amongst family and friends. They started to use the product because we used the product and as they experienced the same reduced friction, they became more dedicated users.

This represented business model leverage in action, which in turn led to an accumulating advantage for PayPal, since they didn’t need to exert energy to expand use cases or acquire new users. Our seamless experience via the marketplace caused us to push the product out and increase usage on our own accord. It became a no brainer that PayPal had something special, and after conducting further due diligence we invested in the company and still hold this position today.

Disregarding Valuation Completely Will Hurt Returns in the Long Run

While this post has revolved around “not only considering valuation”, it is not meant to convey that we “completely disregard valuation”. We believe that valuation should always be considered, albeit in the proper context, when making investment decisions. Like Buffett and Graham, we firmly believe that “price is what you pay; value is what you get.” We would prefer to always pay the lowest price for the greatest amount of future value, but we also realize that we are human and don’t have the foresight to always pay the lowest price.

As such, it is paramount that investors understand the circumstances as to why they may be willing to pay up for an asset and at what price that asset would no longer be an attractive purchase.

While investing in attractive businesses with superior products, visionary management, and massive market opportunities helps us gain qualitative comfort, there is always a certain point where the valuation of an asset will significantly impair future returns.

In the book, Value: The Four Cornerstones of Corporate Finance, an analogy is used that is important to understand:

Suppose a company can invest $1,000 in a factory and earn $200 every year. If the first investors paid $1,000 for their shares, they will earn 20% per year ($200 / $1,000). Suppose then they sell their shares at the end of the first year and a second buyer pays $2,000 for the shares. The new buyer will only earn $200 / $2,000 or 10% ROIC.

This example continues with what McKinsey calls the “Expectation Treadmill”.

The speed of a treadmill represents the expectations built into a stock price. If the company beats expectations continually and the market believes the improvement is sustainable, the stock price will go up (in essence capitalizing the future value of this incremental improvement). However, these new expectations accelerate the treadmill. As performance improves, so does the treadmill’s speed and the company has to run faster to keep up and maintain its new stock price. This treadmill describes the difficulty of continuing to outperform the market. Eventually, analysts will set expectations so high that they will be impossible to achieve and the company’s stock price will fall when they miss.

We believe that when investors completely disregard valuation they may get lucky on a few swings, but overtime this strategy will end in disaster. Typically investors who don’t consider valuation, or don’t know how to, lack the overall business judgement necessary to make value creating investment decisions.

Investing in companies without understanding valuation is another way of saying that valuation doesn’t matter, which leads investors to not only pay too much for companies, but worse yet pay high prices for average assets that lack business model leverage.

While we believe rich valuations must sometimes be paid for best-in-class assets, we know with certainty that there are many highly valued “hyper growth” equities that will assuredly disappoint investors in the future.

Case Study: Twilio (NYSE:TWLO)

1) Reduce Friction in Core Markets 2) Use Core Market Dominance to Expand Into Adjacent Markets

Twilio (TWLO) is an exceptional software asset that has performed well over the past several years. Investors who have purchased TWLO based on sound qualitative and quantitative diligence have been rewarded, whereas those whom have remained gun shy due to “lofty” valuation have missed out on above market returns.

While the below section focuses exclusively on TWLO stock performance, it does not serve as an outlier example. Many quality securities have exhibited similar, and even superior, results over the past several years and have benefited investors who have married valuation work with appropriate qualitative insights.

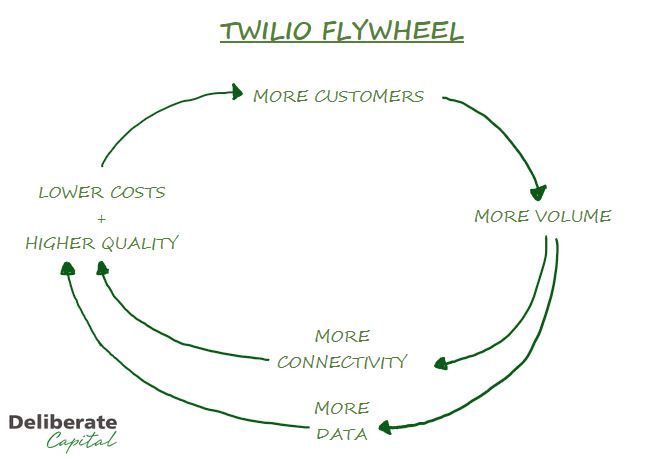

Reduced Friction in Core Market – TWLO exemplifies a company that dramatically reduced friction in its core market. The Company expertly addressed communication, which is not only a basic need for humanity, but more so a critical function for businesses to effectively serve their customers. TWLO’s programmable communications cloud provided such a superb customer experience, that they were able to effectively start a wildfire: If a company wanted to keep up with consumer expectations surrounding real-time communication, they were best off using TWLO to seamlessly handle such needs.

Examples of TWLO use cases – Airbnb uses TWLO to automate SMS messages around guest bookings and confirmations; Lyft/Uber use TWLO to inform customers when their ride has arrived

Like most fantastic businesses, TWLO was laser focused on a core market, which allowed them to reduce customer friction via a superior product offering. Jeff Lawson (TWLO Founder & CEO) made the decision to nail the core market use case, since he realized that any sore of market expansion opportunities would only be made available through a customer base that was entrenched via a superior product experience.

Core Market Dominance Leads to Expansion Opportunities – TWLO’s core market dominance has not only allowed for stellar revenue growth, but more importantly has also generated superior customer insight. Since the company genuinely understands customer habits and behaviors, they are able to take asymmetric bets to expand into adjacent markets. TWLO’s strong customer insight, curated by a stellar core product, lets them develop the following mental model:

“Since we know our customers benefit tremendously from product X and we can track this usage overtime, we have a high degree of confidence they will also benefit from product Y. Thus, we should either focus our time on building product Y or search for companies that do product Y well and buy them.”

Like many other great companies, TWLO has displayed the uncanny ability to expand their TAM via strategic acquisitions. They acquired SendGrid which added an adjacent market opportunity tethered to email, and most recently TWLO announced the acquisition of Segment, which further expands their TAM by harnessing the power of customer data. While we won’t go into the direct implications of this acquisition, it presents an opportunity that could richly reward TWLO for years to come.

Possible to See the Present Clearly – At the time of IPO, it was easy to see that the fundamental desire for customers to communicate with connected devices had staying power. While we couldn’t predict what products TWLO would offer in the future, we could see that their core platform helped customers produce a better communications experience. As digital transformation and device proliferation grew, this core use case became increasingly critical to most organizations. Insight around the present allowed investors to gain comfort with a market leader that had strong potential of remaining relevant for the next decade via accumulating advantages and scale.

Returns Have Been Tethered to Entry Point, But Long Term Returns Have Proven to Be Attractive Even if High Multiples Were Paid

TWLO has vastly outperformed the overall market since their 2016 IPO. The charts above show that TWLO experienced multiple compression that began in the summer of 2016.

In theory, this would have been a great entry point for investors who would have avoided the rich revenue multiples observed directly following the public offering.

In practice, it was much harder to know exactly when multiples would contract, so the more likely scenario was the drop in valuation allowed investors who had previously paid “a high price” to expand their position.

When an investment exhibits periods of downward volatility we like to refocus back on the core thesis:

Does the product offering continue to reduce friction in core markets?

Is management taking advantage of core market dominance and continually looking to expand into adjacent markets?

If the investment thesis hasn’t changed, investors should not worry about short term underperformance, but instead invest additional capital.

With that being said, investors have still been rewarded even if they paid high multiples directly following the IPO and didn’t average down (which is valid due to a variety of factors). Below we outline 3 different scenarios identifying return profiles associated with various entry points:

September 2016 (~24x NTM EV / REV) = ~5.0x return / 46% CAGR

May 2017 (~6x NTM EV / REV) = ~14.8x return / 112% CAGR

March 2019 (~16x NTM EV / REV) = ~2.8x return / 77% CAGR

Investors who remained disciplined and continually allocated capital to TWLO have found their performance to dramatically outpace the market. But even investors who purchased in September 2016 (high valuation) have realized market beating returns.

We can’t tell any one investor how he or she should invest, but hopefully this guide will help you more thoughtfully approach individual company analysis by digging deeper than surface level valuation analysis.

Disclosure: The Authors are currently long Twilio (NYSE:TWLO) and PayPal (NASDAQ:PYPL).