Never Look at Valuation in Isolation (Part I of II)

Investors can become overly reliant on valuation metrics, which can silently kill portfolio returns if analyzed in isolation

Note: This is part I of a II part series. To read part II, click the link below

Too Long, Didn’t Read? Quick Highlights:

Comparing investing styles such as value investing vs. growth investing is a trivial pursuit; focus on opportunities that present a high probability of compounding equity at above market rates over the long-term. Sometimes these are found by buying the out of favor company, which is extremely cheap in the short run, but it’s long term prospects are still favorable even if misunderstood by others right now. Other times, this is found by buying the market winner, which can be expensive in the short run and requires hefty cash outlay, but over the long run the business creates tremendous value leading to exponential returns

Don’t assume because a company is valued at a higher multiple vs. “comparable companies” that it is overvalued. Often times, these comparable companies are selected by Wall Street equity research teams with broad generalizations and are not actually comparable to the target company being valued. Such comparables will often possess different long-term market structures (smaller market size, higher fixed costs, more/less competitive threats) that drastically impact future cash flows. In order to generate above-market returns, investors must properly consider long-term market structures in order to assess potential business value

Short term metrics often don’t matter. They can signal short term performance trends, but the strongest companies consistently perform over the long-term

Technological progress and slowing population growth is resulting in greater downward deflationary pressure compared to upward inflationary pressure from increased borrowing and loose monetary supply. Increased technological adoption, coupled with slowing population growth, could result in longer duration of interest rate suppression, which ultimately would result in higher valuation multiples for companies across all sectors.

Value Investing vs. Growth Investing

We are often asked, “Are you value investors or growth investors?”

Our answer is always the same, an unwavering and automatic, “Yes.”

Why does the general public always compare value investing vs. growth investing as polar opposite approaches?

In order to unpack this, it is important to understand a major cornerstone of financial theory, the capital asset pricing model (CAPM).

Developed in the early 1960s by Jack Treynor, William Sharpe, John Linter, and Jan Mossin, the main idea behind the CAPM is that an individual investment contains two types of risk. As an investor, you can reduce the 2nd risk (company specific risk) by increasing the number of investments in your portfolio, widely known as diversification:

Systematic Risk – General market risk or risk that cannot be diversified away

Example: interest rates, recession, global pandemics, politics, wars, etc.

Company Specific Risk – Risk related to an individual security

Company missing/beating earnings, management changes, competition, etc.

A layman’s explanation of the CAPM is, “Don’t put all your eggs in one-basket”. By avoiding a concentrated basket, an investor theoretically avoids consequences associated with falling and breaking all eggs, which is the financial equivalent of investing solely in a single asset and realizing an unrecoverable–and severe–loss.

While it is commonly accepted that diversification reduces risk and investors don’t need to be able to understand a complicated model to know that, where the CAPM can be helpful is estimating expected returns for an individual stock.

According to the CAPM, for a well-diversified investor, all the risk/return of a single investment can be measured by one factor, denoted by the Greek letter beta. Beta represents how much a stock price moves relative to overall market fluctuations. A stock with a beta above 1.0 will move more than the market on average and a stock with a beta under 1.0 will move less than the market on average.

While the CAPM theory is beautiful in principal, it doesn’t always work in practice as some studies demonstrate that beta fails to explain expected returns vs. actual returns.

In 1992, Eugene Fama and Kenneth French published a paper demonstrating that adding in additional factors (or measurements of risk) better explains the relationship of expected individual stock returns vs. actuals returns. One of the factors that Fama and French added was called “the value factor”. This measured a company’s price-per-share-to-book-value-per-share and revealed that stocks with low multiples produced higher returns than those with higher multiples.

After Fama and French published this new model, value investing took on new meaning. In many investor’s minds, value investing became analogous with buying low multiple stocks and completely shunning assets with high multiples.

As investors get caught up in the idea that value investing = buying low multiples, we believe this is a somewhat flawed methodology. We agree with Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger’s explanation for this conundrum when they were asked the following at a Berkshire Hathaway annual shareholder meeting.

Attendee: “You’ve often stated that value and growth are opposite sides of the same coin, would you care to elaborate on that and do you prefer…growth or value?”

Buffett: “Actually, I think you may be misquoting me, but what I’ve really said is that growth and value are indistinguishable, they’re part of the same equation. Our position is that there is no such thing as growth stocks or value stocks the way Wall Street portrays them as being contrasting asset classes”

Munger: “We are especially partial to laying out large sums of money under circumstances where we won’t have to be smart again. In other words, if we buy good businesses, run by good people at reasonable prices, there’s a good chance that you people (investors) will prosper for many decades… you can say in a sense that’s growth stock investing”

We view the value vs. growth debate as non-sensical and define both value/growth investing as “opportunities that present us with a high probability of compounding equity above market rates over the long-term”.

This means that valuable companies are bought for prices today that will appreciate meaningfully over the long term. Whether these companies are growing revenue, earnings per share, or cash flow at 3%, 30%, or 300%, our goal is always the same:

Find value where our invested equity will be worth much more in 5 – 10 years than it is today.

Sometimes, finding value might be buying the out of favor company, which can be cheap in the short run, but it’s long term prospects are still favorable even if misunderstood by others right now.

Other times, finding value equates to buying the market winner, which is expensive in the short run and requires a decent cash outlay right, but it has a business model which will bring exponential returns in the long run. (Inherent network effects, expanding TAM, superior brand, world class management team, etc.)

Valuation Must Always be Understood in Proper Context

As religious rap fanatics, we both have a strong appreciation for the Wu-Tang Clan and the revolutionary impact they had on music. Their ferocious style, raw attitude, grimy beats, and intellectually flavored expression represented a new style of rap that changed the genre forever. By listening to their music for years, we feel it appropriate to submit that Wu-Tang’s lyrical wisdom extends far beyond the NYC streets and pertains directly to investing.

When making an investment decision, the number one consideration is always, “Is this Wu-Tang Clan approved?”

“Cash, Rules, Everything, Around, Me. C.R.E.A.M. Get the money. Dollar, dollar bill y'all.”

- Wu-Tang Clan

Active investors are taught to treat the quantitative aspects of investing with the utmost respect since a company’s current valuation, what an investor pays for today, has the ability to make or break investment outcomes. But just because a company is valued at a “high” or “low” multiple doesn’t mean an investor is dramatically overpaying or conversely getting a bargain.

Remember that the present value of an asset’s future cash flows is all that matters.

Despite cash being the most important aspect of investment analysis, estimating the exact cash flows of a business can be extremely tricky (especially when considering high growth internet and software assets that require heavy upfront fixed costs to reach proper scale in highly competitive markets). As a result, many investors resort to the default short hand valuation method and instead of analyzing cash flow, will look at valuation multiples (an expression of market value relative to a key statistic that is an assumed value driver, i.e. revenue) vs. other similar companies. (If you need a primer on valuation multiples, we suggest you read the following from UBS)

An everyday example of using valuation multiples is when you purchase a home. The listing will not only offer the final purchase price but also quote the price in terms of price per square foot. (Price being the market value and square footage being the relevant statistic)

Given the simplicity of calculating multiples, there are money managers who will allocate capital solely based on where an asset “currently trades” (EV/Revenue, EV/EBITDA, P/E) vs. comparable assets. While these managers are trying to implement a quantitative metric to decide if something is “over-valued” or “under-valued”, we believe implementing a strict rules-based approach without considering the context of the company’s key qualitative measures (total addressable market (TAM), competition, growth potential, competitive advantages, quality of management, etc.) tends to hurt long-term returns. Valuation alone will often prevent an investor from buying into a market leading company or lead an investor to sell outperformers far too early.

Below we dive deeper into valuation multiples and provide examples of when we believe they are useful and when they are not.

When Valuation Multiples Work | Tract Housing

Analyzing most suburban areas around any major city in the USA, you’ll notice that there are geographic regions where homes look similar.

These developments, known as Tract housing, evolved shortly after WWII when the demand for cheap housing projects grew exponentially as consumers were willing to sacrifice customization in order to own a home. Developers realized that standardized design and construction lowered costs and generated additional profit.

Not only are the houses physically all the same, but residents of the housing development are exposed to the same communal factors that affect real estate prices (i.e. quality school system quality, community job growth, unemployment, crime rates, and weather).

This scenario is ideal for using valuation multiples since standardization allows for direct comparability across homes. If house #1 is selling for $300k and house #2 is selling for $800k, there is either something drastically wrong with house #1 or house #2 has received additional work, resulting in increased value. (Or house #1 is undervalued and house #2 is overvalued. But, by examining a few more houses, the most likely scenario can easily be determined.)

Since developers generally control the housing input variables and they focus on minimizing differences to save costs, using multiples will work in this scenario and nearly anyone with internet access and elementary arithmetic skills can determine if a house is over/undervalued.

When Valuation Multiples Get Tricky | Public Companies With High Growth Rates

While the example of Tract housing and valuation multiples is fairly straightforward, it’s interesting to see this same concept applied to public market investing, even if a business lacks proper comparable companies. Below is a recent set of public companies that are being used by a major Wall Street investment bank’s equity research department to value Twilio (A company operating in the communication as a service market)

What is important for readers to realize, is that this specific equity research team picked the peer group for Twilio to be software companies that are growing revenue +15% per year.

If you agreed with this selection process by the equity research team, a conclusion investors could make is that Twilio is overvalued given it’s trading at a higher revenue multiple in 2020 and 2021 vs. it’s peers (Twilio 29.1x/22.0x vs. the peer median of 26.3x/20.4x).

This conclusion misses a key concept, all of these companies operate in very different subsectors, which has a major implications on the long-term cash flow profile of each business.

While there are plenty of aspects where this analysis goes wrong, and we won’t highlight all of them, a few stand out:

Avalara is being used as a comp, but in comparison to Twilio it has ~1/3 the size of revenue, is growing ~20% slower (on that smaller base), has 18% higher gross margins, but 7% lower EBITDA margins, (implying there are different cost structures in the business models) and it operates in the tax compliance software market that is ~13x smaller than Twilio’s market

Alteryx is being used as a comp, but in comparison to Twilio it has ~1/3 the size of revenue, is growing ~31% slower (on that smaller base), has 36% higher gross margins, 5% higher EBITDA margins, and operates in the data science and analytics market that is ~2x smaller than Twilio’s market

Without diving deep into Twilio’s business, a quick example of why these differences matter is clear when investors look at gross margin differences and market sizing.

Twilio requires more infrastructure to service its revenue and has costs that are hard to remove (they have to pay carriers to send messages and make calls), which results in lower gross margins in the short term, however this also can be a barrier to entry for competitors since Twilio has already achieved the scale necessary to charge less than potential new entrants while maintaining a higher quality service. Twilio’s market is also larger as customers view communication-as-a-service as a growing need and are willing to spend more in the sub-category. This gives Twilio more demand and potential revenue than a company like Avalara or Alteryx who operate in smaller markets with slower growth.

Using only valuation metrics in this context is basically comparing two homes, home #1 in San Francisco and home #2 in Denver and stating that they are a good proxy for valuation since both areas have a technology industry that provides local jobs.

Remember that the present value of the future cash flows of a business is what fundamentally matters.

We know we are really emphasizing this point, but if companies are operating in different markets, with different cost structures, different growth rates, and different long-term scale opportunities, trying to use a sole multiple for valuation is not only lazy but also signals a fundamental lack of diligence and understanding.

The next time you hear someone say something similar to the following: “Wow…30x revenue! XYZ company is soooo overvalued,”

Respond with these questions: “Why do you think 30x revenue makes XYZ company overvalued?” and “What do you think the appropriate valuation is for this business?”

If we had to guess, based on many conversations with other investors, they’ll most likely respond in the following way:

“XYZ business is trading at a very high multiple in comparison to its peer group (or the entire market, a certain index, etc.)”

Investors must flex the appropriate quantitative and qualitative muscles and avoid solely evaluating simple trading metrics vs. peers. Failure to evaluate deeper considerations, such as developing thoughts around the long term cash impacts of a business/market, often leads to short-sighted decisions that negatively impact long term returns.

Relying On Short Term Quantitative Metrics is Dangerous

We admire Brad Gerstner and what he and his team have done at Altimeter Capital. His insight is valuable in understanding how short term metrics shouldn’t be relied on as sole investment criteria. Brad recently spoke to Scott Wapner on CNBC where he said the following:

“I wouldn’t pay that much attention to the next twelve months… you and Cramer like to talk about 100x sales, but when you are analyzing a company that is growing over 100%, with such low penetration of its current TAM, that this company has, you really need to look out three years to figure out what you are really paying for the business. Compare the multiple 3 years from now with the multiple of the rest of the software complex and it looks far less onerous.”

In this context, Gerstner is specifically discussing Snowflake (NYSE:SNOW), but his point is relevant to our overall discussion on valuation. Evaluating growth companies at current trading levels (taking a short term perspective) can be quite dangerous as these metrics do not account for value that will be extracted from via continued market penetration and possible long-term market expansion.

We believe the following forward looking considerations MUST be evaluated when analyzing valuation multiples (especially revenue multiples of fast growing businesses):

A Company’s growth profile in relation to its ultimate market size and penetration rate. There is a difference between a company growing yearly revenue at 50% in a $100Bn market and a company growing yearly revenue at 50% in a $25Bn market. We lean towards companies that have strong growth prospects in massive markets, the opportunity to expand into adjacent markets, and currently low market penetration with an expectation that this penetration will increase as a result of a fundamental structural shift

A Company’s growth profile in relation to its market leadership position and market structure. There is a difference between a company that is growing as the #2 market player and a company that is the established #1 player and expanding to further cement dominance. The power of being #1 in certain respective market coupled with an efficiently sustained growth profile is staggering, especially when considering the winner-take-most scenario that often exists in certain markets

A Company’s growth profile in relation to how efficiently the business model funds such growth. If two companies are growing yearly revenue at 100% we would rather invest in the company that is spending $1 for every $2 of revenue earned as opposed to the company that is spending $2 to earn $2 in revenue

Advancement in Technology is Putting Deflationary Pressure on Interest Rates, Which Influences Multiples Across All Sectors

During every market rally (especially in 2020) click bait type articles seem to appear on major financial news sources with headlines similar to the following, “You Should Brace For a Market Correction as the S&P 500 is at its Highest P/E Multiple Ever”. Similar to the point above about how investors shouldn’t look at valuation in isolation for specific companies, this same logic applies to the overall market.

The forward looking P/E ratio on the S&P 500 is currently ~23.0x vs. the last 10 year average of ~16.4x. While this may seem quite expensive in the short term, we believe this is in part due to how rapid technological progress is putting downward pressure on inflation/interest rates, with lower interest rates equating to higher multiples.

Lower interest rates allow investors to accept a lower earnings yield while still compensating for additional market risk

If a rational investor is stuck deciding between investing in US Treasuries (risk free rate) or investing in the market as a whole (S&P 500), they want to ensure they receive compensation for bearing the additional risk associated by investing in the market.

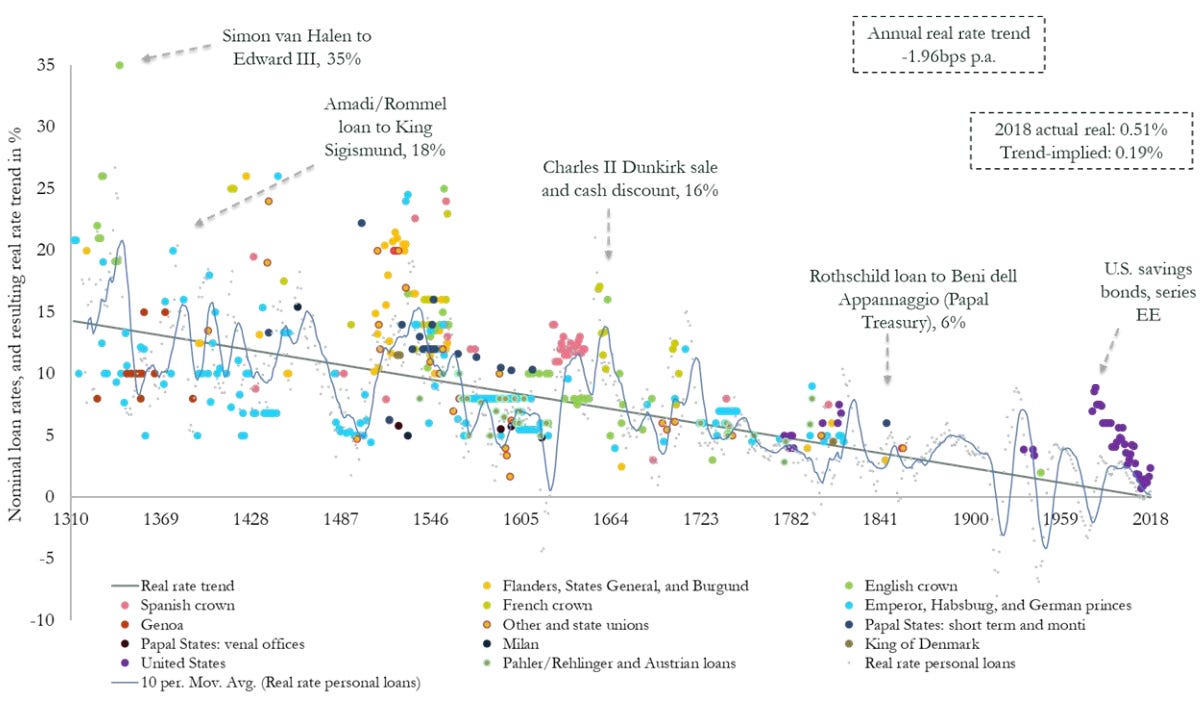

While the nominal 10 year rate has been steadily declining for the past 7 centuries, if the last 20 years are analyzed, it can be observed that rates have averaged between 4 – 5%. In order to understand a reasonable multiple to be paid for being in the market vs. choosing riskless Treasuries, an investor wouldn’t want to buy the S&P 500 if the earnings yield (inverse of the P/E ratio) was less than the risk-free rate, as this wouldn’t offer compensation for the additional uncertainty surrounding market returns. Historically this means that if an investor paid anything over ~20x - 25x forward earnings, they would probably be overpaying (1 / 4% = 25x) to be invested in the market vs. treasuries.

However, if the 10 year treasury is yielding less than 4 – 5%, and if we expect the risk-free rate to be lower, say in 2 – 3% band for the next 5 – 10 years, investors could pay ~33x – 50x forward for the S&P 500 and still be properly compensated.

We expect rates to stay suppressed due to technologic advancements

Through analyzing long term interest rate trends, it is observed that they have been on a downward trajectory for the last 700 years. While periods of short term volatility have been associated with this trend, there is no historical evidence to suggest this will reverse. Folks who believe rates must mean-revert higher may be misunderstanding the long term trend.

A fantastic explanation of the downward interest rate trend comes from Brad Slingerlend, co-founder of NZS Capital. Instead of paraphrasing him, we will directly quote a portion of his article that possesses adequate logic and scope. (Link to his article here as we highly recommend reading it)

“The main inflationary fear right now is that excess liquidity from COVID-driven fiscal and monetary stimulus will be the source of that inflation. And, there can be short-term shocks which cause inflation – e.g., war can reduce oil supply and drive up prices, or a drought can increase crop prices. There are also localized bubbles of long-term structural inflation, e.g., US healthcare costs.

But…let’s try to take a first principles look at systemic, structural inflation – in particular, long-term price increases on the scale of hundreds of years.

Why would prices go up, on average, for everything over a prolonged period of time? I couldn’t really find an answer that made sense to me when I researched this question (and, let's generously say that my degree in economics was less helpful here than my degree in astrophysics; so, to be clear: I am guessing here). So, here is my interesting, simple hypothesis: a long-term cause of structural inflation would be upward pressure from population growth, which would be offset by downward pressure from technological progress. A growing population outpacing the production of goods and services (produced/provided for their own consumption) and leveraging their growing wealth would cause inflation, while technological progress (i.e., making more for less) would offset inflation. Seems reasonable, right?”

The human population went from 400 million to nearly eight billion in the last ~600 years. One of the reasons for population growth was the burgeoning expansion of the economic pie. A dash of Renaissance, a touch of Enlightenment, and a heavy pour of science and the Industrial Revolution all created a lot of hope for the future – and a lot more people. There was more to go around, and people believed that there would be even more to go around in the future. When you believe the future will be bigger than the present, you are also more inclined to borrow and invest in that future.

Inflation over this 600-year period has been a little over 1% on average., however, sustainable inflation has been the highest over the last 60 years, at around 2%, which corresponds to a period when aggregate borrowing in the US (both public and private sector) went from around 1.5x GDP to around 3.5x GDP. So, there seems to be at least a modest correlation between a significant increase in borrowing and an increase in inflation (borrowing driving up inflation makes intuitive sense, since lenders are conceptually printing money)

So, what has been the overriding deflationary pressures that account for this recent decline? The pace of technological development has been massively accelerated and global population growth has slowed. Over the last 60 years, the annual global population growth rate has dropped from around 2% to a little over 1%. And, in the US, the birth replacement rate has been steadily falling to the point where, without immigration, the US population would be shrinking marginally.

Let’s turn briefly to potential systemic, sustained deflationary pressures we might face, which are a little easier to guess at. Advances in technology, as well as improvements in productivity, are constantly giving us more for less. While we might have a period of oil price shocks, green energy will solve that long term. As the economy becomes increasingly digital, from less than 10% now, to 100% over the coming decades, and as AI increases, we will see unprecedented deflationary pressures. Look at what’s happened just this year – thanks to broadband, our houses have become offices, gyms, schools, etc. – talk about a lot of technologically-enabled bang for your buck!

Putting all the variables together, we see inflationary pressure from increased borrowing and deflationary pressure from slowing population growth and increased technological progress.” - NZS Capital, August 2020

While there are many variables integrated into this puzzle and it’s something that many highly qualified people study everyday, (surely more experienced and specialized than us) Slingerlend answers this daunting, and rather complex, question with a fairly straightforward answer.

In practice, we view a great example of his point is computer memory costs over time. The chart below displays how technological acceleration and improvement corresponds directly to a reduction in both storage and memory prices.

As technology continues to be a larger factor in our daily lives, and as companies continue to innovate and harvest technological development, we believe we may see long term interest rates remain lower for prolonged periods, ultimately leading to higher valuation multiples across all industries.

Note: This is part I of a II part series. In part II, we discuss the following topics:

Disruptive markets can transform into much larger opportunities than originally forecasted

While we can't forecast the future with 100% accuracy, we can attempt to properly evaluate the present

No… we aren’t suggesting investors ignore valuation (but instead be more thoughtful) as a complete disregard is almost certain to hurt returns

Case study on a historically “expensive” company that has outperformed

If you liked this post and want to receive future updates directly in your inbox, please subscribe!