Counter Positioning – The Often Underrated Business Power Law

How to defeat an incumbent who appears unassailable by conventional metrics of competitive strength and what boxing teaches us about the power law

Too Long, Didn’t Read? Quick Highlights:

In 1974, Muhammad Ali defeated George Foreman in the classic heavyweight boxing match known as “Rumble in the Jungle”. Ali fought a very unorthodox, yet strategic, fight by standing on the ropes for most of the fight. George Foreman, the undefeated world champion and more powerful fighter, was unable to detect any genius on the part of Ali and sapped his strength by relentlessly attacking. In the end, Ali knocked Foreman out and emerged victorious by strategically using Foreman’s strength against him; this move became known as the “rope-a-dope”.

Most dominant companies of the modern era have employed, albeit with varying degrees of efficacy, a rope-a-dope like strategy known as counter positioning. The strategy of counter positioning was created by Hamilton Helmer and discussed in detail in his book 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy. Counter positioning refers to when a newcomer adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business. It possesses the following common characteristics:

An upstart develops a superior heterodox business model

That business model has the ability to successfully challenge well-entrenched and formidable incumbents

The steady accumulation of customers for the upstart, all while the incumbent remains seemingly paralyzed and unable to respond

Counter positioning is an extremely deceptive and potent power law as success prevents incumbents from detecting and properly diagnosing challenging threats. The adage of “if it’s not broken, don’t fix it” proves costly for even robust businesses that fail to possess, and adequately act on, the fear of disruption. This is one of the reasons that Helmer claims counter positioning to be “his favorite form of power”, it takes strength born from success and cultivates fatal weakness.

Boxing can once again serve as an illustrative example of how success, and failure to take a long-term view, can prove costly. Mike Tyson was a generational fighter who had perhaps the most dominant early career in combat sports history. Unfortunately, Tyson’s career ended in forgettable fashion, in part due to the complacency and short-term gratification that accompanied his early success. Floyd Mayweather on the other hand, fought for 20+ years and retired with an all-time best 50-0 record. Mayweather maintained a singular long-term focus and was able to advance his boxing via stylistic adaptation. Such adaptation allowed Mayweather to understand potential disruption and properly avoid it.

Gillette Case Study – Gillette’s failure to properly diagnose, and act on, the threatening business model of DTC razor companies by being focused on short term profitability significantly hurt long term staying power.

Netflix / Blockbuster Case Study – Blockbuster’s failure to adequately understand the importance of reducing customer friction coupled with a business model dependent on high margin late fees proved to be fatal.

Rumble in the Jungle

“He won’t have it, he knows his whole back’s to these ropes… It don’t matter he’s dope” – Eminem, “Lose Yourself”

On October 30, 1974, 60,000 anxious and energetic fans packed the outdoor “Stade du 20 Mai” in Kinshasa, Zaire to watch what many proclaim to be history’s greatest heavyweight title fight, “Rumble in the Jungle.” The long awaited match featured Muhammad Ali vs George Foreman, but what may surprise you is it wasn’t Ali, but rather Foreman, who was the overwhelming favorite.

In fact, betting odds gave Foreman a massive 3-1 edge to win the fight and for a good reason; he was the current world champion and had won 24 consecutive fights by KO. Even more impressive was that Foreman had won eight fights in a row in the first two rounds; to put it bluntly, George Foreman was absolutely destroying opponents.

What made Foreman so dangerous was his ferocious fighting style that was based off devastating power. Foreman was a unanimous top 5 heavy hitter of all time, and some experts even rank his punching power above that of Mike Tyson (who is known for heavy hitting). This generational power gave Foreman a physical and mental edge over most challengers, as opponents would soften once they felt the first few brutal shots. But as you may know, Muhammad Ali wasn’t like most fighters, and for this match he was strategic on how to use Foreman’s strengths against him.

The beginning of the bout played out with Ali bringing the fight to Foreman, but he quickly retreated back to the ropes as Foreman’s power began to seem insurmountable. This seemed to play to Foreman’s strength as Ali was a stationary target and Foreman began to chop away at Ali with vicious body shots. Everyone watching couldn’t believe Ali was retreating to the ropes, as it resembled a recipe for disaster. Round after round, Ali hung to the ropes and tried to absorb the violent flurry of power punches. With Foreman’s power, many feared it was only a matter of time before Ali was done.

And then something started to change, as the fight went on Foreman began to tire. By the eighth round it was clearly noticeable that Foreman was exhausted and in a blink of an eye Ali’s strategy finally made complete sense. Ali, whom had been on the ropes for a majority of the fight, quickly spun off and unleashed a flurry of quick, precise, and packed punches. Foreman was sent to the mat, couldn’t beat the count, and “The Greatest” reclaimed the heavyweight title.

Ali had won the fight by sitting on the ropes and allowing Foreman to literally punch himself out. This move was coined the “rope-a-dope” by Ali’s trainer as it made Foreman look like a complete fool. Foreman used his supreme advantage, power, the entire fight, but from the beginning of the bout Ali strategically countered in a manner that Foreman, nor most viewers, could detect.

Ali took Foreman’s greatest strength and turned it into the ultimate weakness by employing a method that Foreman was not acquainted with or expecting.

Counter Positioning – The Rope-a-Dope Technique of the Business World

Ali’s same tactics against Foreman are just as effective when utilized by companies in the ring of business. Think of how many quality businesses have been disrupted by challengers who offered a product, service, or delivery model that was completely foreign to the existing competitive arena. In fact, most dominant companies of the modern era have employed, albeit with varying degrees of efficacy, a rope-a-dope like strategy known as counter positioning.

Counter positioning is a business strategy power created by Hamilton Helmer and discussed in detail in his book 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy. We view 7 Powers as one the best business strategy books ever written and highly recommend studying it (if you haven’t already) and applying it in your investing or business management processes. We strategically evaluate our investments via the seven power laws Helmer lays out as it helps us gain confidence in identifying long-term compounders.

Before we dive in further, it is important to understand the distinction between power and strategy as defined by Helmer:

Power = The set of conditions creating the potential for persistent differential returns

Strategy = A route to continuing power in significant markets

While most strategic thought pieces focus exclusively on scale, network effects, branding, etc., Helmer’s thinking around counter positioning has profound insight that we believe is severely underutilized and underappreciated by the broader investing community.

Counter Positioning = A newcomer adopts a new, superior business model which the incumbent does not mimic due to anticipated damage to their existing business

Common Characteristics of Counter Positioning:

An upstart develops a superior heterodox business model

That business model has the ability to successfully challenge well-entrenched and formidable incumbents

The steady accumulation of customers for the upstart, all while the incumbent remains seemingly paralyzed and unable to respond

Upstart Benefit = The new business model is superior to the incumbent’s model due to lower costs and/or the ability to charge higher prices (i.e. adds additional value to the consumer either through lower costs or larger perceived benefit)

Incumbent Barrier = Collateral damage to their existing business profitability.

Incumbents common reaction patterns:

Denial

Ridicule

Fear

Anger

Capitulation (frequently too late)

Counter positioning is rather complex when compared to other business strategy concepts, and complexity is often-times difficult for existing businesses to grasp. This complexity stems first from the introduction of a new business model on the part of a challenger, which by definition should be foreign to existing players.

“There are few occurrences in business as complex as the emergence and eventual success of a new business model…. In situations like this, it falls to the strategist to carefully peel back the layers of complexity and eventually seize upon some irreducible kernel of insight amidst the competitive reality.” – Hamilton Helmer, 7 Powers

Counter positioning is also complex due to the fact it doesn’t unfold overnight and generally takes years of disciplined execution for the power to fully be harvested by a challenger. It took several years for Netflix to overtake and dispose of Blockbuster, and it took Walmart over a decade to finally take action to attempt defending against Amazon in the form of acquiring Jet.com.

Lastly, and perhaps most important, psychological complexity arises from incumbent failure to initially recognize the threats of a potential new business from the poison of success and failure to strategically evaluate the long-term. This convolution leads incumbent businesses to make calculated business decisions that they think are prudent, but in reality are extremely damaging.

“The Incumbent’s failure to respond, more often than not, results from thoughtful calculation. They observe the upstart’s new model, and ask ‘Am I better off staying the course, or adopting the new model?’” – Hamilton Helmer, 7 Powers

The Poison of Success and Failure of Long-Term Vision

Counter positioning is an extremely deceptive and potent power law as success prevents incumbents from detecting and properly diagnosing challenging threats. The adage of “if it’s not broken, don’t fix it” proves costly for even robust businesses that fail to possess, and adequately act on, the fear of disruption. This is one of the reasons that Helmer claims counter positioning to be “his favorite form of power”– it takes strength born from success and cultivates fatal weakness.

As referenced above, capitulation from incumbent businesses often occurs too late and the challenger has already created a critical mass that is capable of producing powerful business fission. Strategic reasoning is difficult even for the most seasoned of executives and often times bias prevents them from stepping back and changing the pre-diagnosed plan of attack. This failure to properly reason is what ultimately cost George Foreman the title against Ali….once he realized his strength was sapped the battle had already been lost.

In his book “Think Like a Rocket Scientist”, Ozan Varol (a legitimate rocket scientist) dedicates Chapter 9 to the poison of success and relays the following points:

“Success is the wolf in sheep’s clothing. It drives a wedge between appearance and reality. When we succeed, we believe everything went according to plan. We ignore the warning signs and the necessity for change. With each success, we grow more confident and up the ante.”

“The moment we think we’ve made it is the moment we stop learning and growing. When we’re in the lead, we assume we know the answers, so we don’t listen. When we think we’re destined for greatness, we start blaming others if things don’t go as planned. Success makes us think we have the Midas touch–that we can walk around turning everything into gold.”

“This is why child prodigies unravel. This is why the housing market, believed to be the bedrock of the American economy, crumbled. This is why Kodak, Blockbuster, and Polaroid flamed out. In each case, the unsinkable sinks, the uncrashable crashes, and the indestructible self-destructs–because we assume their previous success secures their future.”

Jeff Bezos understands the damage of success as well as perhaps any manager and in his 2016 Letter to Shareholders succinctly expounded on its dangers:

“I’ve been reminding people that it’s Day 1 for a couple of decades. I work in an Amazon building named Day 1, and when I moved buildings, I took the name with me. I spend time thinking about this topic.

Day 2 is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death. And that is why it is always Day 1.”

Businesses, like the humans that create and operate them, are complex adaptive systems. The power to adapt and change business models stems from conscious human choice. It is when companies realize this early on that the resulting flexibility delivers increased potential for longevity. Boxing once again can offer an illustrative example of how long-term planning and adaption can ensure success by avoiding disruption. This time we will look at Floyd Mayweather and compare him to Mike Tyson, both terrific fighters, but two very different career outcomes.

Mike Tyson, like George Foreman, was powerful, but also had overwhelming speed, body movement, and incredible footwork. Mike became the youngest heavyweight champion of all time in 1986 (20 years old) and for the next four years, and at the height of his power, seemed indestructible. Tyson won his first 19 fights by way of knockout, with 63% of those knockouts occurring in the first round. This rise to stardom occurred at supersonic speed and Tyson was universally regarded as “The Baddest Man on The Planet”.

Then, in 1990, Tyson lost the heavyweight championship to a massive underdog, Buster Douglas, in the 10th round of their Tokyo-based fight. Tyson seemed weakened and exposed as the fight went on, and although Mike would reclaim the heavyweight title in 1995, the blueprint for how to beat him had been drafted.

If patient boxers could survive Tyson’s initial onslaught, and proceed to push him into the deeper waters of later rounds, their chances of beating him increased dramatically.

In subsequent years, Tyson was beaten by Evander Holyfield twice (1996 & 1997), and was viciously knocked out by Lennox Lewis in 2003 before ending his career with two embarrassing losses (Danny Williams and Kevin McBride).

Floyd Mayweather took a different approach to his 21 year career (1996 - 2017). Not only did Mayweather sport a 50-0 professional record, but he had the highest plus-minus ratio in recorded boxing history (this means Mayweather is not only the most accurate puncher of all time, but is also the best at avoiding getting hit). Mayweather’s early career was marked by speed, accuracy, and pure competence… he was knocking opponents out because he was simply more skilled, faster, and extremely reflexive.

But Father Time started to catch up with Mayweather, and as he continued to fight, he realized that longevity would be predicated upon his ability to transform his fighting style through adaption. So he adapted and became the undisputed GOAT of impregnable defensive technique and counter punching. This stylistic adaptation was so effective that at 36 years old Mayweather utterly embarrassed a 23 year old Canelo Alvarez (whom by the way is one of the most dominant boxers of the modern era).

Tyson and Mayweather were both blessed with God given talent, yet their overall careers took dramatically different paths. While Mike Tyson’s dominant stretch was assuredly impressive, his career will always be marked by a crash and burn-like decline. His rapid success fabricated a feeling of invincibility and through the associated internal and external forces (Don King), he developed a poisonous and fallacious belief that ultimately damaged his legacy.

Mayweather on the other hand executed the second half of his career with near perfect strategic awareness, and at times, brilliantly employed counter positioning.

But more importantly, Mayweather understood the fight game from a perspective of totality and worked to prepare for disruption and counter positioning.

Such comprehension made him hyper-aware of how to approach young, competent, and dynamic challengers and helped Money Mayweather diagnose his career as a complex adaptive system. These diagnostic measures yielded remarkable longevity and success; Mayweather fought until he was 40 years old, retired having amassed 26 consecutive world title victories, and took virtually no physical damage.

This is one of the reasons why long-term focus is imperative for companies to be compounding machines. Not only does a business model based on the long-term set young companies up well for effectively employing the strategy against incumbents, but it also fosters a sense of adaption and anti-fragility for market leaders to offer protection against counter positioning.

This is why we make it a top priority to look for executive teams that habitually, and incessantly, remind the world that their focus is on the long-term.

For example, Jeff Bezos is so fanatical about the long-term that over the years he has ensured every shareholder letter includes a copy of the 1997 letter which outlined his long-term vision.

“We will continue to make investment decisions in light of long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term profitability considerations or short-term Wall Street reactions.”

We believe that companies with a long-term vision have a massive strategic advantage over the vast majority of publicly traded companies. Success can occur very quickly in the public markets and, more times than not, such rapid prosperity is associated with short and immediate term drivers. Companies that give heed to such short-term gratification run the risk of setting themselves up for disruption from several avenues, including that of counter positioning. The treadmill of expectation via short-term share price increase, fast profits, and Wall Street praise moves at such an accelerated clip that companies fear what will happen if they take their eye off the short term ball.

Legendary investor Nick Sleep relayed this point in his 2009 Nomad Partnership Letter to investors:

“It is perhaps the dominant, get-ahead mindset of our times and it is inherently focused on vivid, short term outputs. Sales targets and profit margins achieved through cutting corners may be inherently worthless in the end, but they can dazzle for a while, and that is their value to the locker room set.”

In our view, companies that are able to avoid the enticing prospect of the short term are better advantaged to adapt, refine, and never lose their original ambition. It is our expectation that such businesses will have a career similar to that of Floyd Mayweather, and as long-term investors, this is our overwhelming preference.

Gillette – When Additional Engineering Fails to Deliver Customer Value

The Gillette company was founded in the late 19th century when salesman and inventor King Camp Gillette created the first safety razor that used disposable blades as an alternative to the traditional straight razor. Unlike the straight razor which required frequent sharpening and a high level of skill to avoid injury while using (thus often only used by barbers), the safety razor was marketed to the common man as an alternative to frequent barber trips.

Despite this new design, Gillette’s initial market for mass razor adoption was unclear. The company only sold 51 razors and 168 blades in its first year as a two or three day stubble was generally accepted by the public (or at least overlooked without too much comment). In 1917 this all changed as President Woodrow Wilson declared war on the Central Powers and America was thrust into World War I.

This historic event altered the razor market forever as military regulations required that every solider have their own shaving kit. Gillette’s compact and easy to use design was quickly adopted and Gillette sold over 1.1 million razors in 1917 alone, far outpacing sales of any straight razor.

One year later, the U.S. military began issuing Gillette shaving kits to every U.S. serviceman and the company’s sales quadrupled to 3.5 million razors and 32 million blades. Far more important than a one-year sales spurt, the habit of shaving was perpetually engrained into these young men. When soldiers returned from the war, Gillette reinforced advertising to emphasize the brand name, making sure that shaving and Gillette were perceived as one and the same.

Despite new competition from copy cat razor companies, Gillette maintained its leadership in the shaving space by increasing its spending on marketing and R&D. Each time a patent ran out, Gillette would introduce a differentiating product feature.

In the 1980s, Gillette reportedly spent more than $200 million to develop the Sensor, a razor with tiny springs that allowed each blade to move separately from one another. This was a response to the expiration of its patents on the double-edged safety razor, the “tiltable” safety razor handle, and the blade guard, among others. As patents expire on meaningful innovations — and said innovations become industry standards — they have to be replaced with new, less meaningful ones that give an updated competitive edge.

– The Vox, “The absurd quest to make the ‘best’ razor”

In 2019, at Gillette’s Global Innovation Summit, they announced a $200 heated razor, and described it as the ultimate shaving experience. "By fusing beautiful form with reimagined function, the Heated Razor from GilletteLabs truly elevates the shaving experience.”

Despite these additional “product innovations,” Gillette was fighting a losing battle. Consumers didn’t need or even want product innovation. In 1917, the consumer needed a better shave experience, but after the 1980s, shaving was just that…shaving! Gillette was trying to solve a problem that consumers didn’t view as a problem anymore. These consumers we’re left with a new problem, that is, frustration over paying $6.25 per replacement blade on a shaving experience that wasn’t improving.

According to this reviewer, Gillette appears to be ignoring their founder’s motto, “We’ll stop making razor blades when we can’t keep making them better.”

2010: Enter DollarShaveClub.com

“Hi, I’m Mike, founder of DollarShaveClub.com. What is DollarShaveClub.com? Well, for $1 per month we send high quality razors right to your door. Yea! $1.

Are the blades any good? No…our blades are f**cking great.”

The idea for DollarShaveClub came when Mike Dubin met his co-founder Mark Levine at a party in 2010. The conversation took an unexpected turn, and before long, Mark was asking Mike for help selling 250,000 razors he had acquired from Asia. This gave Mike an idea. What if he started a service that would eliminate the expense and hassle of selling razor blades? What if they just showed up at your door each month for $1 each?

The value proposition to consumers was pretty straight-forward. Alongside eating and showering, shaving is one of the regular things most of us do on a frequent basis and razors are unnecessarily fancy and expensive. Mike’s idea was to help consumers save time by auto shipping the razors once per month and help consumers save money by keeping the cost low vs. Gillette.

This new product offering resonated with consumers. By July 2012, another company (Harry’s) entered the space to compete with Gillette on a similar plane. Gillette was suddenly losing its brand name appeal that they built during WWI and shaving was no longer predominantly associated with Gillette.

Gillette, in hopes of smashing these new upstarts, decided to fight back through legal action.

Gillette ordered hundreds of dollars’ worth of Harry’s razors immediately upon the company’s launch, apparently to examine them before suing for patent infringement.

The patent in question was filed in 1998 and described an invention simply called “Razors”; Gillette asked for a jury trial and reparations in the amount of three times the damages of lost sales. The case was dismissed in less than a week.

This did not stop Gillette from pursuing further litigation. In December 2015, the company filed a patent infringement suit against DollarShaveClub. In the filing, Gillette alleged that the manner in which its competitor was coating its razor blades to maintain sharpness was in violation of a 2004 patent, asking that the state of Delaware immediately block the sale of all DollarShaveClub razors. DollarShaveClub filed a countersuit two months later, and both were dropped.

– The Vox, “The absurd quest to make the ‘best’ razor”

In 2014, Gillette had ~70% market share of the US grooming market (which they had held steady since pre-2000s). By 2016, DollarShaveClub’s revenue had grown to ~$200mm per year and was bought out by Unilever for $1bn. Harry’s revenue figures rose at a similar pace (estimated revenue between $300mm - $400mm in 2018).

Gillette’s market share erosion was inevitable.

In 2017, Gillette, after failing to stem their market erosion from lawsuits, product innovation, or marketing campaigns, they responded by slashing the price of their replacement blades by ~20%. They wrote an apologetic blog post trying to spin the move as customer centric, “You told us our blades can be too expensive and we listened,” but a few years later we’d know the real reason. By 2019, Gillette’s parent company recorded an $8bn write-down of Gillette’s business and current estimates peg Gillette’s US market share under 50%.

While the shaving wars will continue, this example illustrates the importance of using counter positioning as a business strategy tactic. Just as Muhammad Ali used George Foreman’s strength against him in the boxing ring, DollarShaveClub and Harry’s used Gillette’s market share dominance and margin profile against them.

In the early days, Gillette could not have responded by lowering their prices. They spent too much money on both R&D and sales & marketing and management did not want to give up their high margin business because a few startups wanted to compete with them. They also needed their product margins to be sustained in order to support their own stock price and for management to hit their bonus targets (remember that most managers are paid bonuses yearly, so they are incentivized for short term performance vs. long-term sustainability).

If Gillette chose to lower prices, they would have cannibalized their own business, drastically slashing profit, and resulting in a lower business value (and stock price).

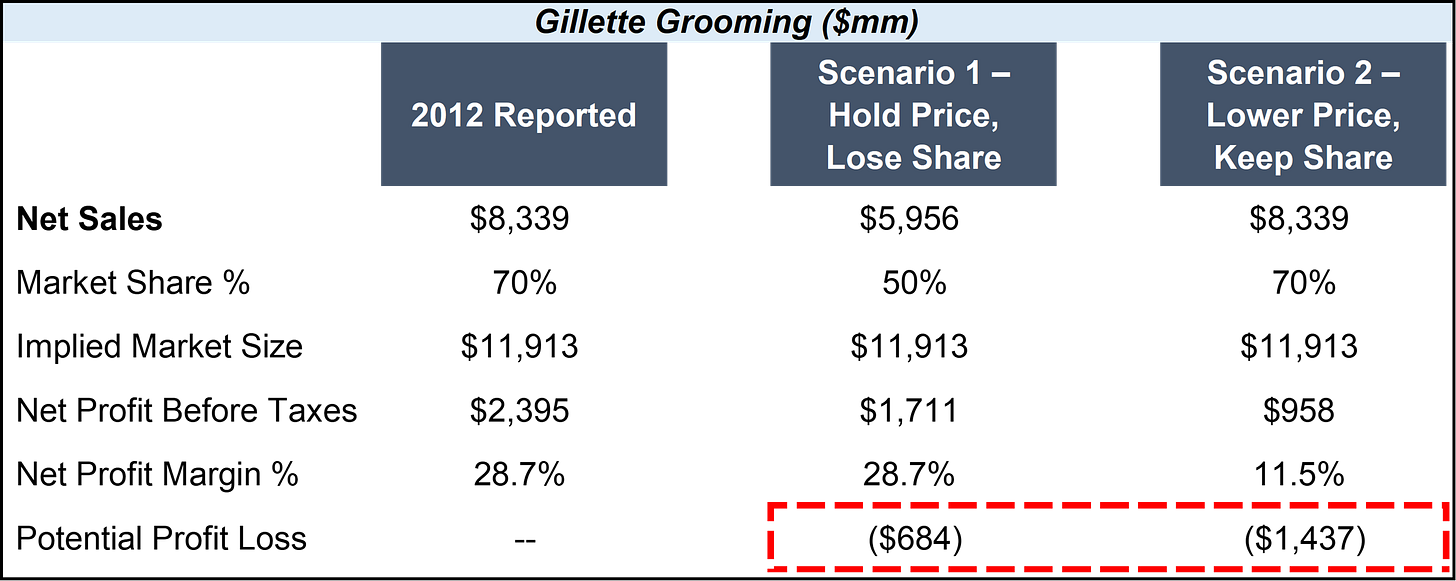

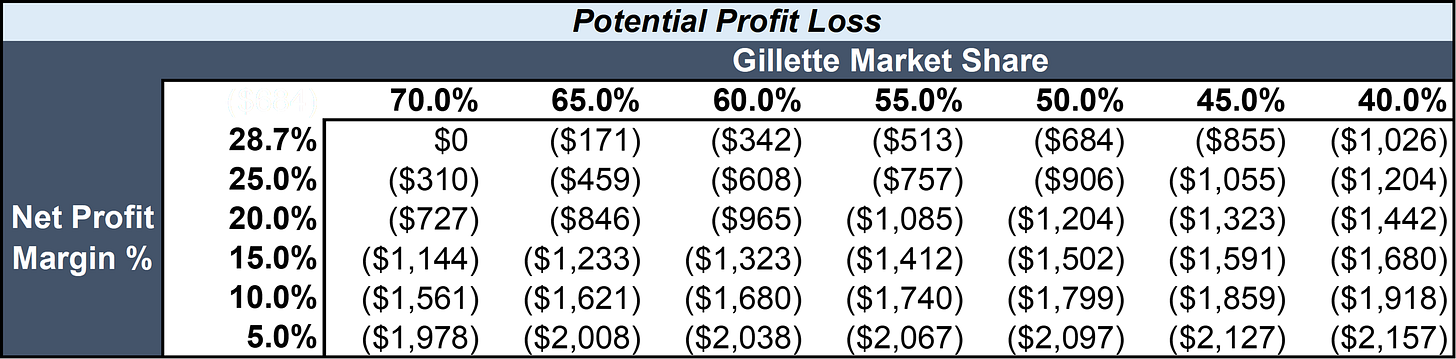

To illustrate this point for better understanding, we looked at Gillette’s 2012 reported financials and ran two scenarios:

Gillette keeps prices the same but loses market share or

Gillette lowers prices to compete but keeps market share

This quick scenario/sensitivity analysis shows why it took Gillette so long to reduce prices.

In the intermediate term, lowering prices to compete would incur more profit losses than keeping prices the same and losing market share.

Remember Helmer’s framework for incumbents reactions

Denial

Ridicule

Fear

Anger

Capitulation (frequently too late)

Gillette followed Helmer’s framework for incumbent reactions and by 2017 they reached the capitulation stage. Market share had eroded far enough and management finally accepted the need to lower the price of some of their blades in order for business to survive.

What is interesting is that Gillette is currently straddling its strategy. While some of their blades (Gillette G5) are now competitively priced vs. Harry’s/DollarShaveClub, Gillette’s focuses consumer’s attention to their ProGlide lines, which carry a premium price tag.

We don’t believe this strategy for Gillette is sustainable in the long-term and ultimately view the “shaving wars” as a perfect example of how young, and disruptive, companies can use counter positioning to their advantage.

The Fall of Blockbuster

Originally, Reed Hastings (CEO of Netflix) would tell people that he got the idea for Netflix in 1997 when he returned Apollo 13 to Blockbuster a few days late and was charged a $40 late fee. Co-founder Marc Randolph later confirmed that the story was made up, but the explanation for Netflix’s rise still holds true.

When Netflix launched in the late 90s, Blockbuster was the undisputed champion of video rentals with 3,000+ locations around the world and over $4bn in revenue.

By 2000, Netflix had seen some traction as customers loved the idea of renting multiple DVDs at a time, keeping them for as long as they wanted and paying the same fixed $16 per month with no late fees. The only issue was that Netflix was still burning through cash and had only achieved a measly $5mm in revenue.

Hastings and co-founder Marc Randolph had an idea to sell Netflix to Blockbuster as Netflix needed the cash to fund their business and they had the online expertise Blockbuster was lacking. Hastings and Randolph flew out to Dallas to meet with Blockbuster CEO John Antioco and the following interaction took place.

Reed: “There are certainly areas where Blockbuster could use the expertise and market position that Netflix has obtained to position itself more strongly. We should join forces, we will run the online part of the combined business. You will focus on the stores. We will find the synergies that come from the combination, and it will truly be a case of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts.”

Antioco: “The dot-com hysteria is completely overblown, the business models of most online ventures, Netflix included, just weren’t sustainable.”

“If we were to buy you, what are you thinking? I mean, a number. What are we talking about here?”

Reed: “Fifty million”

Through Reed’s pitch, Randolph had been watching Antioco. Randolph had seen Antioco use all the tricks that he also learned over the years: lean in, make eye contact, nod slowly when the speaker turns in your direction. Frame questions in a way that makes it clear you’re listening. But now that Reed had named a number, Randolph saw something new, something he didn’t recognize, his earnest expression slightly unbalanced by a turning up at the corner of his mouth. It was tiny, involuntary, and vanished almost immediately. But as soon as Randolph saw it, he knew what was happening: John Antioco was struggling not to laugh.

Vanity Fair, Inside Netflix’s Crazy, Doomed Meeting with Blockbuster

Despite being rejected by Blockbuster, Netflix was able to manage its cash position until it went public in May 2002. What Antioco didn’t realize was that by rejecting Netflix, Blockbuster set themselves up for failure. By 2007, Antioco departed as CEO after 3 years of falling revenue and by 2010 Blockbuster had filed for bankruptcy (Netflix was worth ~$24bn at the time).

In hindsight, the downfall of Blockbuster seemed inevitable and Antico failing to entertain the $50mm purchase of Netflix was a mistake. But what most people fail to consider is that Antioco at the time could not have bought them without sacrificing Blockbuster’s own business performance.

Blockbuster generated ~15-20% of its revenue by charging late fees (very high margins) and its movie rentals we’re not cheap at $2-$8 per movie (depending on the geography). Blockbuster also had much higher real estate costs given their requirement for a geographic footprint and they needed to keep prices high to support this cost structure and subsequent stock price.

These operational factors were coupled with the fact that Antioco was not the founder of Blockbuster, so short term compensation incentives outweighed long term business success (To read more about this idea, read our previous article on Why We Prefer Founder-led Companies).

The main takeaway is that Reed Hastings and Netflix effectively implemented counter positioning against Blockbuster. Netflix had a superior business model which Blockbuster could not have copied without crippling their fundamental business.

While it’s pure conjecture on our part, we believe Hastings knew that Blockbuster was never going to buy them. Hastings wrote the foreword in Helmers book 7 Powers, so if anyone understood counter positioning, it was Hastings himself. Equally impressive, Netflix used counter positioning again via streaming and the creation/ownership of original content to take on the media conglomerates.

“I'm not concerned with noise because I'm playing the long game.”

– Jay-Z

Really enjoyed the article. I would like to ask whether counter-positioning is specifically chosen as a strategy from the start or whether it's something that arises out of the pursuit of innovation? Perhaps, it's a mix of both. In the example of Mayweather, it seems his fighting style was not necessarily developed purposefully to "counter-position" against opponents but came to fruition with an intent to stay in the game as long as possible.

Anyway, your style of writing is pleasantly easy to read and I'm looking forward to reading more as a first-time reader!